19 nov 2019

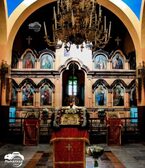

A group of fanatic Israeli colonialist settlers stormed, on Monday at night, the al-Maskobiyya Church, known as Abraham’s Oak Holy Trinity Monastery, in Hebron city, in the southern part of the occupied West Bank.

Eyewitnesses said dozens of illegal colonists, accompanied by a large military force, invaded the Christian Monastery while chanting and singing, before holding prayers in the church.

The Monastery, located in the al-Jilda Street in Hebron city, in an area that falls under the complete control of the Palestinian Authority.

All of Israel’s colonies in occupied Palestine, including those in and around occupied Jerusalem, are illegal under International Law and the Fourth Geneva Convention, and constitute war crimes.

Also, Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention states: “The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.” It also prohibits the “individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory”.

Eyewitnesses said dozens of illegal colonists, accompanied by a large military force, invaded the Christian Monastery while chanting and singing, before holding prayers in the church.

The Monastery, located in the al-Jilda Street in Hebron city, in an area that falls under the complete control of the Palestinian Authority.

All of Israel’s colonies in occupied Palestine, including those in and around occupied Jerusalem, are illegal under International Law and the Fourth Geneva Convention, and constitute war crimes.

Also, Article 49 of the Fourth Geneva Convention states: “The Occupying Power shall not deport or transfer parts of its own civilian population into the territory it occupies.” It also prohibits the “individual or mass forcible transfers, as well as deportations of protected persons from occupied territory”.

31 oct 2019

Photograph Source: View of the Holy Sepulchre, Jerusalem. Berthold Werner – CC BY-SA 3.0

by Ramzy Baroud

Palestine’s Christian population is dwindling at an alarming rate. The world’s most ancient Christian community is moving elsewhere. And the reason for this is Israel.

Christian leaders from Palestine and South Africa sounded the alarm at a conference in Johannesburg on October 15. Their gathering was titled: “The Holy Land: A Palestinian Christian Perspective”.

One major issue that highlighted itself at the meetings is the rapidly declining number of Palestinian Christians in Palestine.

There are varied estimates on how many Palestinian Christians are still living in Palestine today, compared with the period before 1948 when the state of Israel was established atop Palestinian towns and villages. Regardless of the source of the various studies, there is near consensus that the number of Christian inhabitants of Palestine has dropped by nearly ten-fold in the last 70 years.

A population census carried out by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics in 2017 concluded that there are 47,000 Palestinian Christians living in Palestine – with reference to the Occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip. 98 percent of Palestine’s Christians live in the West Bank – concentrated mostly in the cities of Ramallah, Bethlehem and Jerusalem – while the remainder, a tiny Christian community of merely 1,100 people, lives in the besieged Gaza Strip.

The demographic crisis that had afflicted the Christian community decades ago is now brewing.

For example, 70 years ago, Bethlehem, the birthplace of Jesus Christ, was 86 percent Christian. The demographics of the city, however, have fundamentally shifted, especially after the Israeli occupation of the West Bank in June 1967, and the construction of the illegal Israeli apartheid wall, starting in 2002. Parts of the wall were meant to cut off Bethlehem from Jerusalem and to isolate the former from the rest of the West Bank.

“The Wall encircles Bethlehem by continuing south of East Jerusalem in both the east and west,” the ‘Open Bethlehem’ organization said, describing the devastating impact of the wall on the Palestinian city. “With the land isolated by the Wall, annexed for settlements, and closed under various pretexts, only 13% of the Bethlehem district is available for Palestinian use.”

Increasingly beleaguered, Palestinian Christians in Bethlehem have been driven out from their historic city in large numbers. According to the city’s mayor, Vera Baboun, as of 2016, the Christian population of Bethlehem has dropped to 12 percent, merely 11,000 people.

The most optimistic estimates place the overall number of Palestinian Christians in the whole of Occupied Palestine at less than two percent.

The correlation between the shrinking Christian population in Palestine, and the Israeli occupation and apartheid should be unmistakable, as it is obvious to Palestine’s Christian and Muslim population alike.

A study conducted by Dar al-Kalima University in the West Bank town of Beit Jala and published in December 2017, interviewed nearly 1,000 Palestinians, half of them Christian and the other half Muslim. One of the main goals of the research was to understand the reason behind the depleting Christian population in Palestine.

The study concluded that “the pressure of Israeli occupation, ongoing constraints, discriminatory policies, arbitrary arrests, confiscation of lands added to the general sense of hopelessness among Palestinian Christians,” who are finding themselves in “a despairing situation where they can no longer perceive a future for their offspring or for themselves”.

Unfounded claims that Palestinian Christians are leaving because of religious tensions between them and their Muslim brethren are, therefore, irrelevant.

Gaza is another case in point. Only 2 percent of Palestine’s Christians live in the impoverished and besieged Gaza Strip. When Israel occupied Gaza along with the rest of historic Palestine in 1967, an estimated 2,300 Christians lived in the Strip. However, merely 1,100 Christians still live in Gaza today. Years of occupation, horrific wars and an unforgiving siege can do that to a community, whose historic roots date back to two millennia.

Like Gaza’s Muslims, these Christians are cut off from the rest of the world, including the holy sites in the West Bank. Every year, Gaza’s Christians apply for permits from the Israeli military to join Easter services in Jerusalem and Bethlehem. Last April, only 200 Christians were granted permits, but on the condition that they must be 55 years of age or older and that they are not allowed to visit Jerusalem.

The Israeli rights group, Gisha, described the Israeli army decision as “a further violation of Palestinians’ fundamental rights to freedom of movement, religious freedom and family life”, and, rightly, accused Israel of attempting to “deepen the separation” between Gaza and the West Bank.

In fact, Israel aims at doing more than that. Separating Palestinian Christians from one another, and from their holy sites (as is the case for Muslims, as well), the Israeli government hopes to weaken the socio-cultural and spiritual connections that give Palestinians their collective identity.

Israel’s strategy is predicated on the idea that a combination of factors – immense economic hardships, permanent siege and apartheid, the severing of communal and spiritual bonds – will eventually drive all Christians out of their Palestinian homeland.

Israel is keen to present the ‘conflict’ in Palestine as a religious one so that it could, in turn, brand itself as a beleaguered Jewish state in the midst of a massive Muslim population in the Middle East. The continued existence of Palestinian Christians does not factor nicely into this Israeli agenda.

Sadly, however, Israel has succeeded in misrepresenting the struggle in Palestine – from that of political and human rights struggle against settler colonialism – into a religious one. Equally disturbing, Israel’s most ardent supporters in the United States and elsewhere are religious Christians.

It must be understood that Palestinian Christians are neither aliens nor bystanders in Palestine. They have been victimized equally as their Muslim brethren, and have also played a major role in defining the modern Palestinian identity, through their resistance, spirituality, deep connection to the land, artistic contributions and burgeoning scholarship.

Israel must not be allowed to ostracize the world’s most ancient Christian community from their ancestral land so that it may score a few points in its deeply disturbing drive for racial supremacy.

Equally important, our understanding of the legendary Palestinian ‘soumoud’ – steadfastness – and of solidarity cannot be complete without fully appreciating the centrality of Palestinian Christians to the modern Palestinian narrative and identity.

Ramzy Baroud is a journalist, author and editor of Palestine Chronicle. His latest book is The Last Earth: A Palestinian Story (Pluto Press, London, 2018). He earned a Ph.D. in Palestine Studies from the University of Exeter and is a Non-Resident Scholar at Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies, UCSB.

by Ramzy Baroud

Palestine’s Christian population is dwindling at an alarming rate. The world’s most ancient Christian community is moving elsewhere. And the reason for this is Israel.

Christian leaders from Palestine and South Africa sounded the alarm at a conference in Johannesburg on October 15. Their gathering was titled: “The Holy Land: A Palestinian Christian Perspective”.

One major issue that highlighted itself at the meetings is the rapidly declining number of Palestinian Christians in Palestine.

There are varied estimates on how many Palestinian Christians are still living in Palestine today, compared with the period before 1948 when the state of Israel was established atop Palestinian towns and villages. Regardless of the source of the various studies, there is near consensus that the number of Christian inhabitants of Palestine has dropped by nearly ten-fold in the last 70 years.

A population census carried out by the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics in 2017 concluded that there are 47,000 Palestinian Christians living in Palestine – with reference to the Occupied West Bank, East Jerusalem and the Gaza Strip. 98 percent of Palestine’s Christians live in the West Bank – concentrated mostly in the cities of Ramallah, Bethlehem and Jerusalem – while the remainder, a tiny Christian community of merely 1,100 people, lives in the besieged Gaza Strip.

The demographic crisis that had afflicted the Christian community decades ago is now brewing.

For example, 70 years ago, Bethlehem, the birthplace of Jesus Christ, was 86 percent Christian. The demographics of the city, however, have fundamentally shifted, especially after the Israeli occupation of the West Bank in June 1967, and the construction of the illegal Israeli apartheid wall, starting in 2002. Parts of the wall were meant to cut off Bethlehem from Jerusalem and to isolate the former from the rest of the West Bank.

“The Wall encircles Bethlehem by continuing south of East Jerusalem in both the east and west,” the ‘Open Bethlehem’ organization said, describing the devastating impact of the wall on the Palestinian city. “With the land isolated by the Wall, annexed for settlements, and closed under various pretexts, only 13% of the Bethlehem district is available for Palestinian use.”

Increasingly beleaguered, Palestinian Christians in Bethlehem have been driven out from their historic city in large numbers. According to the city’s mayor, Vera Baboun, as of 2016, the Christian population of Bethlehem has dropped to 12 percent, merely 11,000 people.

The most optimistic estimates place the overall number of Palestinian Christians in the whole of Occupied Palestine at less than two percent.

The correlation between the shrinking Christian population in Palestine, and the Israeli occupation and apartheid should be unmistakable, as it is obvious to Palestine’s Christian and Muslim population alike.

A study conducted by Dar al-Kalima University in the West Bank town of Beit Jala and published in December 2017, interviewed nearly 1,000 Palestinians, half of them Christian and the other half Muslim. One of the main goals of the research was to understand the reason behind the depleting Christian population in Palestine.

The study concluded that “the pressure of Israeli occupation, ongoing constraints, discriminatory policies, arbitrary arrests, confiscation of lands added to the general sense of hopelessness among Palestinian Christians,” who are finding themselves in “a despairing situation where they can no longer perceive a future for their offspring or for themselves”.

Unfounded claims that Palestinian Christians are leaving because of religious tensions between them and their Muslim brethren are, therefore, irrelevant.

Gaza is another case in point. Only 2 percent of Palestine’s Christians live in the impoverished and besieged Gaza Strip. When Israel occupied Gaza along with the rest of historic Palestine in 1967, an estimated 2,300 Christians lived in the Strip. However, merely 1,100 Christians still live in Gaza today. Years of occupation, horrific wars and an unforgiving siege can do that to a community, whose historic roots date back to two millennia.

Like Gaza’s Muslims, these Christians are cut off from the rest of the world, including the holy sites in the West Bank. Every year, Gaza’s Christians apply for permits from the Israeli military to join Easter services in Jerusalem and Bethlehem. Last April, only 200 Christians were granted permits, but on the condition that they must be 55 years of age or older and that they are not allowed to visit Jerusalem.

The Israeli rights group, Gisha, described the Israeli army decision as “a further violation of Palestinians’ fundamental rights to freedom of movement, religious freedom and family life”, and, rightly, accused Israel of attempting to “deepen the separation” between Gaza and the West Bank.

In fact, Israel aims at doing more than that. Separating Palestinian Christians from one another, and from their holy sites (as is the case for Muslims, as well), the Israeli government hopes to weaken the socio-cultural and spiritual connections that give Palestinians their collective identity.

Israel’s strategy is predicated on the idea that a combination of factors – immense economic hardships, permanent siege and apartheid, the severing of communal and spiritual bonds – will eventually drive all Christians out of their Palestinian homeland.

Israel is keen to present the ‘conflict’ in Palestine as a religious one so that it could, in turn, brand itself as a beleaguered Jewish state in the midst of a massive Muslim population in the Middle East. The continued existence of Palestinian Christians does not factor nicely into this Israeli agenda.

Sadly, however, Israel has succeeded in misrepresenting the struggle in Palestine – from that of political and human rights struggle against settler colonialism – into a religious one. Equally disturbing, Israel’s most ardent supporters in the United States and elsewhere are religious Christians.

It must be understood that Palestinian Christians are neither aliens nor bystanders in Palestine. They have been victimized equally as their Muslim brethren, and have also played a major role in defining the modern Palestinian identity, through their resistance, spirituality, deep connection to the land, artistic contributions and burgeoning scholarship.

Israel must not be allowed to ostracize the world’s most ancient Christian community from their ancestral land so that it may score a few points in its deeply disturbing drive for racial supremacy.

Equally important, our understanding of the legendary Palestinian ‘soumoud’ – steadfastness – and of solidarity cannot be complete without fully appreciating the centrality of Palestinian Christians to the modern Palestinian narrative and identity.

Ramzy Baroud is a journalist, author and editor of Palestine Chronicle. His latest book is The Last Earth: A Palestinian Story (Pluto Press, London, 2018). He earned a Ph.D. in Palestine Studies from the University of Exeter and is a Non-Resident Scholar at Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies, UCSB.

26 oct 2019

Nelson Mandela’s church, the Methodist Church of Southern Africa, this month endorsed Palestine’s Boycott, Divestment and Sanctions movement (BDS).

At a recent conference in Cape Town, the church denounced “Israel’s ongoing ill-treatment and oppression of Palestinian people, and the historic prophetic role played by the church and international community in fighting Apartheid, and any form of discrimination and injustice.”

The church also has communities in Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland and Mozambique – some two million congregants altogether.

Announcing the monumental decision, BDS South Africa pointed out the historic links of the country’s Methodist church to their country’s liberation struggle giant and first democratically-elected president, Nelson Mandela.

Mandela was brought up by a deeply religious Christian mother, and attended a series of Methodist schools throughout his youth.

In his 1994 autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela recounted the often contradictory nature of being brought up in a colonial education aimed at “natives”, such as himself.

“The educated Englishman was our model,” he narrated, “what we aspired to be were ‘black Englishmen,’ as we were sometimes derisively called. We were taught – and believed – that the best ideas were English ideas, the best government was English government, and the best men were Englishmen.”

But, like many religious traditions tied up with colonial empires, the legacy of Methodism in southern Africa contained varying, and sometimes contradictory, tendencies.

As well as these colonial impulses, South African churches were also venues for the liberation struggle.

The most famous figure in this regard is, of course, the Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The Anglican church’s most titanic anti-apartheid veteran is also a vocal critic of the Israeli apartheid against the indigenous Palestinians, which he has described as being even worse than South African apartheid.

But the Methodist church too had its own figures of progress, and the church has long opposed apartheid.

Seth Mokitimi, one of Mandela’s teachers, later became the first black president of a major South African denomination – a move that required courage during the height of the apartheid regime in 1964.

Mandela’s religious convictions stayed with him beyond his childhood. In his memoir, he also recounts being “proselytised” (a tellingly religious term) for communism by “my first white friend,” Nat Bregman.

During Mandela’s early twenties, he and Bregman worked together in Johannesburg at a law firm run by a liberal Jewish sympathiser with the African National Congress (ANC) (whose armed wing Mandela would of course later go on to found).

All his life, and especially during the Cold War, Mandela famously denied being a communist, including during the ‘Treason Trial’ he was subjected to in the 1960s.

But after his death in 2013, both the ANC and the South African Communist Party confirmed (or revealed, depending on your point of view) that he had actually been a member. Indeed, the party stated “Mandela was not only a member of the then underground South African Communist Party, but was also a member of our Party’s Central Committee.”

Be that as it may, Mandela, in Long Walk to Freedom, wrote that Bregman’s entreaties towards joining the party didn’t win him over at the time, and that one of the reasons he did not join was because of his Christianity: “I was also quite religious, and the party’s antipathy to religion put me off.”

The adoption by Mandela’s church, of the BDS movement, then is hugely symbolic.

It is a recognition of how the BDS movement was explicitly modelled on the South African anti-apartheid boycott movement. More than that, it shows, once again, the leading role that South African activists are playing in the global movement for justice in Palestine.

They recognise apartheid when they see it.

The Methodist Church of Southern Africa’s policy on the boycott of Israel is a particularly good one. It instructs Methodists to boycott “all businesses that benefit the Israeli economy,” as BDS South Africa explained.

The church has also called for a “boycott of all Israeli pilgrimage operators and tours” and is urging Christians visiting the Holy Land to instead “deliberately seek out tours that offer an alternative Palestinian perspective.”

These are principled and practical measures that can have an impact on Israel. Slowly, but surely, BDS is making its mark.

Israel now dedicates untold millions of dollars towards fighting BDS – a sign that the strategy is having an effect.

South African churches’ BDS policies are something for us to emulate, and work towards in the West.

Amandla! Awethu!

At a recent conference in Cape Town, the church denounced “Israel’s ongoing ill-treatment and oppression of Palestinian people, and the historic prophetic role played by the church and international community in fighting Apartheid, and any form of discrimination and injustice.”

The church also has communities in Namibia, Botswana, Lesotho, Swaziland and Mozambique – some two million congregants altogether.

Announcing the monumental decision, BDS South Africa pointed out the historic links of the country’s Methodist church to their country’s liberation struggle giant and first democratically-elected president, Nelson Mandela.

Mandela was brought up by a deeply religious Christian mother, and attended a series of Methodist schools throughout his youth.

In his 1994 autobiography, Long Walk to Freedom, Mandela recounted the often contradictory nature of being brought up in a colonial education aimed at “natives”, such as himself.

“The educated Englishman was our model,” he narrated, “what we aspired to be were ‘black Englishmen,’ as we were sometimes derisively called. We were taught – and believed – that the best ideas were English ideas, the best government was English government, and the best men were Englishmen.”

But, like many religious traditions tied up with colonial empires, the legacy of Methodism in southern Africa contained varying, and sometimes contradictory, tendencies.

As well as these colonial impulses, South African churches were also venues for the liberation struggle.

The most famous figure in this regard is, of course, the Archbishop Desmond Tutu. The Anglican church’s most titanic anti-apartheid veteran is also a vocal critic of the Israeli apartheid against the indigenous Palestinians, which he has described as being even worse than South African apartheid.

But the Methodist church too had its own figures of progress, and the church has long opposed apartheid.

Seth Mokitimi, one of Mandela’s teachers, later became the first black president of a major South African denomination – a move that required courage during the height of the apartheid regime in 1964.

Mandela’s religious convictions stayed with him beyond his childhood. In his memoir, he also recounts being “proselytised” (a tellingly religious term) for communism by “my first white friend,” Nat Bregman.

During Mandela’s early twenties, he and Bregman worked together in Johannesburg at a law firm run by a liberal Jewish sympathiser with the African National Congress (ANC) (whose armed wing Mandela would of course later go on to found).

All his life, and especially during the Cold War, Mandela famously denied being a communist, including during the ‘Treason Trial’ he was subjected to in the 1960s.

But after his death in 2013, both the ANC and the South African Communist Party confirmed (or revealed, depending on your point of view) that he had actually been a member. Indeed, the party stated “Mandela was not only a member of the then underground South African Communist Party, but was also a member of our Party’s Central Committee.”

Be that as it may, Mandela, in Long Walk to Freedom, wrote that Bregman’s entreaties towards joining the party didn’t win him over at the time, and that one of the reasons he did not join was because of his Christianity: “I was also quite religious, and the party’s antipathy to religion put me off.”

The adoption by Mandela’s church, of the BDS movement, then is hugely symbolic.

It is a recognition of how the BDS movement was explicitly modelled on the South African anti-apartheid boycott movement. More than that, it shows, once again, the leading role that South African activists are playing in the global movement for justice in Palestine.

They recognise apartheid when they see it.

The Methodist Church of Southern Africa’s policy on the boycott of Israel is a particularly good one. It instructs Methodists to boycott “all businesses that benefit the Israeli economy,” as BDS South Africa explained.

The church has also called for a “boycott of all Israeli pilgrimage operators and tours” and is urging Christians visiting the Holy Land to instead “deliberately seek out tours that offer an alternative Palestinian perspective.”

These are principled and practical measures that can have an impact on Israel. Slowly, but surely, BDS is making its mark.

Israel now dedicates untold millions of dollars towards fighting BDS – a sign that the strategy is having an effect.

South African churches’ BDS policies are something for us to emulate, and work towards in the West.

Amandla! Awethu!